Infobesity

To reiterate a crucial point from part one, it’s not just our bodies and rudimentary biological systems that are shaped by evolution. It’s quite literally everything about us, including the most complex and somewhat metaphysical aspects of ourselves, like our personalities and moral instincts. Even the abject evils of rape and racism have their own evolutionary origin stories.

Indeed, our very minds are a rich and complex evolutionary stew that has been cooking for millions of years in an environment vastly different from the one we now inhabit. Which brings me to what is arguably the greatest example of evolutionary mismatch: hyperconnectivity.

To illustrate this point, let us return to our 24-hour timeline, with anatomically modern humans emerging at midnight: The first newspapers don't appear until around 11:58 PM. Radio doesn't arrive until 11:59:36 PM. Television follows at 11:59:42 PM. And the internet—the tool that would eventually connect nearly every human mind on the planet—doesn't emerge until 11:59:53 PM, mere seconds before midnight.

For the other 23 hours and 58 minutes of our metaphorical day, humans lived in small, intimate groups of perhaps 50 to 150 people. Our ancestors' entire social world consisted of the faces they saw around their fires each night, the neighboring bands they occasionally traded with, and the distant cousins they might encounter a few times each year at seasonal gatherings.

Remember my earlier mention of racism and its evolutionary backstory? Racism, that persistent scourge of humanity, is ultimately a species of tribalism, and tribalism itself is largely a product of our species living in such a quaint and socially limited world for so very long—a world made up of small, isolated, and genetically homogenous groups. For much of human existence, encountering someone with noticeably different phenotypical characteristics was a reliable indication that they belonged to a different and potentially hostile tribe. In other words, our prehistorically designed brains are wired for “stranger danger;” to see people who look noticeably different from us and think "no bueno."

If calorie abundance is a significant novelty, hyperconnectivity is nothing short of profound. We are, at our core, an intensely social species. Throughout our evolution, social standing within the tribe wasn't just about status, it was quite literally a matter of life and death. To be ostracized meant certain death, which is why our brains tend to process social threats with the same urgency as physical ones.

But for virtually all of human history, social dynamics were managed on relatively small scales. Take those tiny communities of 50-150 people in which our ancestors lived. That range isn't arbitrary—it corresponds to an anthropological concept called the Dunbar number: the cognitive limit of stable social relationships humans can maintain. Our Dunbar number, approximately 150, is the largest of any primate and is directly tied to the size of our neocortex. It's quite literally a hardware limitation imposed on the human brain.

So what happens when you take a brain that views social information as existentially critical, and that has evolved over millions of years to navigate social structures smaller than a typical modern neighborhood, and suddenly, within a span of time that represents .01% of humanity’s total existence, flood it with sociopolitical information from billions of people across an entire planet?

Well, we don’t have to imagine anything because we are, in fact, living in this experiment right now. It’s called the 21st century.

According to a robust 2013 study published by the University of Southern California, Americans’ media consumption “has been growing at compounded rates ranging between 3 percent and 5 percent each year.” The study also found that:

In 2008, Americans talked, viewed and listened to media for 1.3 trillion hours, an average of 11 hours per person per day. By 2012, total consumption had increased to 1.46 trillion hours, an average of 13.6 hours per person per day, representing a year-over-year growth rate of 5 percent.

From 2008 to 2015, total annual hours for users of Facebook and YouTube will grow from 6.3 billion hours to 35.2 billion hours, a year-over-year growth rate of 28 percent.

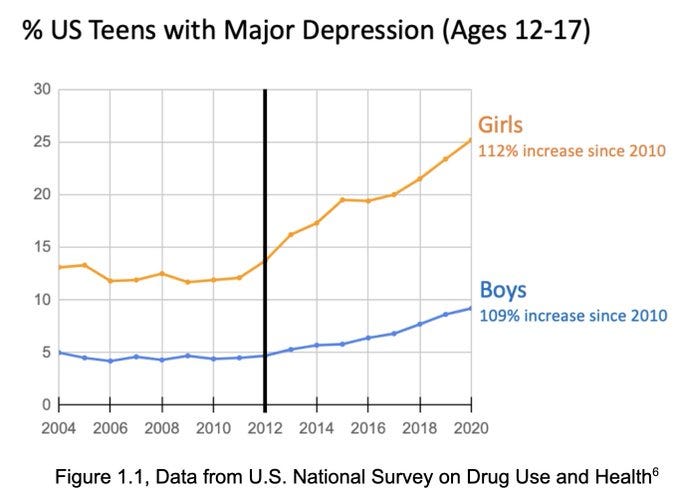

As anyone alive can attest, we humans writ large are not as psychologically fit as we were just a few generations ago. Just as excess calories are disrupting our metabolisms and fueling an epidemic of obesity, excess sociopolitical information exchanged via hyperconnectivity is overwhelming our emotional regulation systems, contributing to a mounting mental health crisis, particularly in the developed world:

And just as modern industry has learned to exploit our disrupted metabolisms and runaway appetites by engineering increasingly addictive food products, it has mastered the art of hijacking our innate desire for emotional stimulation. From the endless status updates flowing from our countless parasocial relationships on social media, to the virtual intravenous drip of outrage carefully curated by 24-hour news networks—which, remarkably, evolved from obscure channels mostly seen in airport terminals into the dominant players in television—we are being force-fed an informational diet designed to trigger our strongest emotional responses.

We are, in a word (one that I wish I had coined), infobese.

If you’re wondering why I keep referring to “social” and “sociopolitical” information, as opposed to information more broadly, it is because it is the former that is especially toxic and addictive. As anyone who lives with teenagers knows, it is not the endless supply of encyclopedic information on plate tectonics or the sacking of ancient Thebes that is sucking up all their time and attention. Anodyne academic information is not the problem. In fact, that virtually all extant knowledge is now instantly and universally accessible via these small devices that we keep in our pockets is undeniably one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

It is sociopolitical information that is the problem: information that concerns how we relate with one another. This is the information on which we are most prone to overdose, as it, among other things, directly engages our limbic system—our threat and reward detection system.

Simply put, we are not wired to know quite so much about quite so many people, even if that knowledge is ultimately superficial. We are not evolutionarily configured to see as many faces as we see on a daily basis, to know what so many people are doing with their lives, even if most of those faces are digital and most of what is shared is a carefully cultivated facade. In the salad days of my youth, merely competing with the various cliques at school could be an all-consuming challenge. It was hard enough when the girls thought they had to compete with Stacey the Cheerleader and the boys with Todd the Quarterback. Today, these poor kids’ brains think they have to compete with every highly filtered Stacey and Todd (and Kardashian) with an Instagram account, regardless of where on the planet they live.

Nor are we wired to process political information at our current scale and intensity. For our ancestors, politics was necessarily local. It was limited, mercifully, to the interpersonal dynamics of relatively small groups. The fate of distant peoples simply couldn't factor into their daily cognitive load. But now we're bombarded with urgent political developments from every corner of the globe, each wrapped in layers of partisan interpretation and delivered with the same emotional urgency as if it were happening in our own neighborhood.

Combining this unprecedented exposure to political information with our hardwired tribal instinct creates a potent admix. We're pattern-matching machines designed to sort people into "us" and "them," a fact that our modern political ecosystem is more than happy to exploit. Every issue, no matter how nuanced, is routinely portrayed as a binary choice between good and evil. Every political opponent becomes an existential threat. And because we're consuming this information through the same neural circuitry that evolved to process immediate physical and social threats, we respond with the same visceral intensity our ancestors reserved for rival tribes encroaching on their territorial boundaries.

And, no, the ironic elephant in the room is not lost on me. I am, indeed, contributing to this problem myself to some extent. Which brings me to my conclusion.

Back Burning

Addictions, and the pathologies that go with them, exist on a spectrum.

Take our food example: on the extreme right end of the spectrum you have the morbidly obese. Those poor souls you see on My 600lb Life. The ones who literally need a forklift to lift them out of bed and who usually end up eating themselves to death. Fortunately, it is unlikely that any of us are those people. But we do, each of us, fall somewhere on the spectrum. The overwhelming majority of us could stand to eat a bit healthier, to shed a few pounds, to take a few inches off our waistlines. We are all afflicted to some degree.

Infobesity is no different. You have the extreme cases, the people with underlying mental health issues whose fragile psyches crumble under the massive wave of sociopolitical information that bombards them literally every day, whose radical personalities are fed a constant stream of information optimized for provocation and radicalization. These are your school shooters, marathon bombers, and political assassins. A cohort, sadly, that seems to be growing exponentially this century.

Mercifully, most of us are not those people. But we are all a bit more addicted than we should be to that little dopamine hit that occurs when we read that breaking news article or that juicy gossip piece, to the exhilaration we feel when our tribe scores a victory or the outrage when they suffer a defeat. Case in point, I’ll be lucky if more than a dozen of you even finish this rather neutral, and arguably tedious, post. Meanwhile, entry 4,586,923 in my KFC Doing Dumb Things series will invariably be read by thousands.

One thing upon which everyone in the Gables seems to agree, is that our local politics has taken a dramatic and recent turn for the worse. Our community is more tribal, divided, and agitated than ever. Every commission meeting, it seems, must now feature a series of incoherent psychotic rantings from at least one deranged lunatic who clearly uses local activism to derive a sense of purpose, while the comments sections of certain local blogs exhibit all the rationality and measure of a Stone Mountain clan meeting.

Moreover, our political discourse has taken on a bizarrely scaled-up tone, from Ariel’s POTUS-LARPing “economic stimulus” and “anti-establishment” rhetoric, to Kirk’s “cesspool of corruption” and umpteen divine light references. Heck, just a few commission meetings ago, we were forced to endure one of Rip Holmes’ videos about the impending nuclear holocaust.

This is local politics?

It is no coincidence that most of this began in earnest right around the time our city’s grassroots fully digitized. Right around the time Ariel the Munibomber debuted his for-profit propaganda machine, Nextdoor fully took root, and WhatsApp became a basecamp for a bevy of resident chat groups.

It is almost as if this tremendous surge in connectivity has affected our community, as if by broadly replacing in-person, face-to-face interaction with impersonal online communication has eroded civility and deepened mistrust. It’s almost as if the exponential increase in local political news consumption has somehow radicalized us, the same way the exponential increase in national political news radicalized the nation writ large. Go figure.

And what’s my role in this, you ask? Am I not guilty, myself, of perpetuating this unfortunate unraveling of the social fabric?

Yup. Sure am.

Then again, Aesop’s Gables is not a but-for element in all of this. As in, “But for this newsletter, Gables politics would be a picture of civic harmony, a scene out of a Norman Rockwell painting.” Sorry folks, but I am not responsible for your appetite for provocative and acerbic political commentary. I merely cater it, as responsibly as I can.

I truly beg your pardon if this sounds presumptuous, but I liken what I do here to something called back burning—the practice of wildfire fighters setting controlled fires to contain a larger blaze. I try to fight inflammatory politics with intentional provocation of my own—but always with purpose, always with thought. To be sure, I'm not pretending to be a neutral observer standing above the fray. I’m simply trying to channel our collective appetite for controversy into something more substantive than pure lizard-brained outrage.

Paint-by-numbers manipulation will always be infinitely easier than thoughtful, earnest argumentation. This newsletter would be infinitely less demanding if I took the Gables Insider or Political Cortadito route—taking partisan opinions, supplementing them with baseless rumors and innuendo, couching them in pseudo-objective language, and calling it "news." Instead of posts with titles like "The Manchurian Manager," I could opt for the more palatable "Residents Grow Concerned Over Manager's Ties to Commissioners." I could try, at least, to Jedi mind-trick your brain into thinking its reading “the news.”

But I don't, because I respect you.

As I always tell people, especially those who cope with their cognitive dissonance by accusing me of being on Lago or Anderson's payroll: No one pays me to do this. But more importantly, while one could theoretically pay me to write nice things about them (they'd have to dig very, very deep into their pockets to make it worth my while), there's no amount of money that could make those nice things true.

Time will tell whether this approach helps snuff or stoke the flames of our tribal politics—or whether it has any effect at all. But I believe understanding how we got here, how our ancient minds are failing us in this hyperconnected age, can only help the cause. Hopefully, we haven't evolved only to devolve.

Excellent read! It's truly disheartening to witness the decline of common sense in our society, where critical thinking seems to have taken a backseat to tribalism and groupthink. The way people anchor their entire belief systems on selectively chosen information, dismissing anything that challenges their views, is deeply troubling. It’s as if many have traded rational discourse for echo chambers, where confirmation bias reigns supreme.

Thanks for the clarity, kid!